Margaret T. Johnson practices law solo from her home in Presque Isle, limiting her practice for the past 16 years to child protective matters and relying heavily on computers. Native to Portland, she is a 1964 graduate of Wellesley College and received her law degree, cum laude, from the University of Maine School of Law, where she was an editor of the Maine Law Review, in 1974. Meg currently serves on the Courts' Protective Custody Oversight Committee. She is founder and past co-chair of the Child Protective Subcommittee of the Family Law Section of the Maine State Bar Association.

Q: What drew you into the legal profession?

A: Hey, it was the Seventies. Everyone who had survived young adulthood in the Sixties went to law school in the Seventies. We wanted a better grasp on what made the country tick, the better to improve it. I'd just survived five years as a naval officer's wife, wearing hats and gloves and making destroyer-sized leis out of nylon net in Honolulu. I'd fried my brain with a diet of Woman's Day and Family Circle.

I'd spent several years as a teacher. I'd liked working with the kids but found the bureaucracy a pain. I'd been out of college long enough to know that Betty Friedan's take on the status of women was accurate. I had two toddler daughters (more to come) and wanted to do what I could to make a better world for them. Our parents, the World War II generation, had driven us nuts. The newspaper want ads still were divided by sex. Pregnancy was grounds for teacher dismissal.

At the time, I thought I was making a reasoned choice. In retrospect, I think I was swept along by a trend so big that it was impossible for an individual to see. A good many choices we make in life are influenced in that way. I probably had to go to law school. So did my then-husband, my present husband and a whole generation of cousins and in-laws, all of whom went to the same law school during the same period.

But lucky me! I loved law school. A jewel of a law school in my own hometown with tuition of $600 per year. Quality day care provided nearly free by the Model Cities program. I wish that opportunities like that were still open. It is what our society can do for people when there is the collective will to do so.

Q: Where did you go to law school and what was your law school experience like?

A: Our whole crew went to the University of Maine School of Law in Portland, Maine. I started in the old school building on High Street and moved to the round tower in the second year. Ed Godfrey was recruiting a terrific faculty and Don Garbrecht was horse-trading to build the library. By the time I started each course, I had heard a great deal about it from family members who had taken it before me, but the first year was still scary until I'd received the first batch of grades and realized I was going to do all right. From there on it was still busy but the terror was gone.

Professors and Caroline Glassman provided paid work and I spent a summer working at the Clinic with Judy Potter downtown. During my second and third years I spent most of my free time as a staff member and then as a member of the board of editors of the Law Review. I published an article on the treatment of pregnancy in the military. I graduated in 1974, third in my class, and took the Bar Exam that summer, during the hearings on Nixon's impeachment. A TV was on constantly in Dean Godfrey's office and those of us who were studying in the library for the bar exam kept congregating in there.

It was during Clinic my second summer of law school that I had my first contact with child protective cases, although neither parents nor children nor caseworkers had representation then. That was what was striking about it. You'd look into one of the normally crowded courtrooms and see two women, one at each desk, looking up at the judge. One of them was talking. She was the caseworker and the other woman was the mother. Fathers weren't usually notified of the proceedings. I learned that notices of subsequent reviews, held infrequently, were mailed to the address the mother had at the outset. Finally, the mother was sent a letter to the effect that, if she didn't respond by a given date, she'd be presumed to have agreed to a termination of her parental rights. Mike Petit, then the Commissioner of the Department of Human Services, signed the consent letter to the Court on the mother's behalf.

Q: After law school, what legal job opportunities were available to you?

A: The short answer to the question is that there was only one legal job available to me in 1974 in the entire southern half of the state. I didn't look then in the northern half.

The career track I hoped for was the normal one for someone performing well in law school at the time. You began interviewing with law firms during the latter half of your second year and worked at a law firm during your second-year summer. Then, during the third year, you applied for a clerkship with the Law Court for the year after law school. Following that additional subsidized education, you returned to work as an associate at the law firm where you had clerked that second-year summer. I had worked my tail off to qualify for that career track.

Before I started sending resumes and setting up interviews, I had no inkling that I was doomed. But from then on for a year and a half, there was nothing but the sound of slamming doors from Saco to Lewiston. Every firm gave me an interview because these were people I had known and socialized with my whole life. And every firm for miles and miles around turned me down. The reason, they said, was that, because I was married to an associate in a Portland firm, my employment would bring the work of two firms to a halt, his and mine.

The Rules of Professional Responsibility then provided that the conflicts of one partner were the conflicts of all partners. My husband's firm had an anti-nepotism policy, so they wouldn't consider me either. Finally, the Law Court turned me down for a clerkship because it routinely heard appeals brought by my husband's firm.

My options then were accounting or life and health insurance, so I gratefully accepted a position in the legal department at Union Mutual, even though I can't say that I had ever before or have since been interested in insurance. I learned a great deal, however, about computer systems and project management and the mechanics of presentations while there. Thence, I went into solo practice in Scarborough for awhile, then joined the Public Advocate's office in Augusta, trying public utility rate cases and insurance rate cases. I learned evidence and the handling of expert witnesses from some of the best trial lawyers in the State of Maine.

One of my carpool mates from Portland to Augusta during that period was Tom LaPointe, who was lobbying into existence Maine's first modern child protective law. Daily, in the car, he worked through those provisions clause by clause until all of us had them memorized.

In 1985, I remarried and moved to Presque Isle, where I have been practicing child protective law out of my home pretty much ever since, whenever I'm not on the road to Augusta for meetings and lobbying someone or other for something. Nowadays, when I see a statute or a rule in my area of expertise that seems unjust, I organize the affected sistren and brethren and go to the source and try to change it.

After the 1973-74 debacle, however, I never had the heart to work for change of that Bar Rule. Sue Kominsky, as soon as she had the opportunity, picked up the issue and secured a revision of the Rules, which narrowed the definition of spousal conflict to the spouse. See Bar Rule 3.4(f)(3) and (4).

Q: Were legal opportunities limited for women at that time?

A: Not formally, except for the Bar Rule mentioned above. But the culture was very different. Only 41 women had been admitted to the Maine Bar in the 102 years from 1872 to July 1974. (See chronological chart.) Because the Board of Overseers registry wasn't created until 1979, it is derived from Paul Mills' research in old Maine Registers, Martindale-Hubbells, and occasional privately published lists. We can't be at all certain that we haven't missed someone, and to those women and their descendants I apologize

and request that they give me a call so we can get it right next time. Of those, only 18 were practicing in July 1974. A minority that small can't dance; it can only do the Token Tiptoe and act grateful to have the opportunity. Consider our numbers then in contrast to the number of women actively practicing law today in Maine ... exactly 1000!

Q: Were there many women practicing law in the State at that time?

A: As stated above, very few in the summer of 1974, about 18. They were spread out across the state and fairly isolated from each other except for a nucleus in Portland. The southern dean and mentor of the Portland group was Caroline Glassman, although she had not been in Maine for a long time. She had moved to Maine from California in the late '60's. In California, she had been a litigator. When she moved to

Portland, she ran the Model Cities Program and then set up a criminal practice out of her home in the West End. That practice was the model for the one I have today, albeit in a different specialty and now with computers --the computer makes a tremendous difference in the time and tedium involved in doing one's own administrative work. In the summer of 1974, she moved her offices into the Old Port.

Judy Potter also had trial experience, in Washington D.C. on women's employment cases before the EEOC and in the federal courts. She stopped in at the old law school building on High Street in the summer of 1972 and Dean Godfrey hired her on the spot. Judy not only ran and expanded the Clinic program, but she continued to consult on her EEOC cases and has personally helped hundreds of us women lawyers by now. Sigrid Tompkins had practiced probate law with Pierce Atwood since 1941.

Mary Kay Brennan was a graduate of University of Maine School of Law in 1971 and was in general practice with her husband Joe downtown. I think Annee Tara was practicing in or near Portland. Kathy Greenleaf supervised outsourced claims litigation nationwide in the legal department of Union Mutual, where she'd been for a year. Bertha Rideout, who had offices in Freeport since 1953, occasionally appeared in the Portland District Court.

Harriet Henry, who had been admitted to the bar in 1954, had been appointed District Court Judge in Portland in 1973. During the preceding years, she had published a multi-volume treatise on environmental law and land use.

The northern dean of Maine women lawyers was Sue Kominsky, who had been practicing in the Vafiades firm since 1966. She was a litigator. Mary Louis Kurr was also practicing in a Bangor firm. She had been admitted in 1972.

Sue Calkins was in the Presque Isle office of Pine Tree Legal Aid; Pat Danisinka-Washburn was with Pine Tree in Skowhegan. Ruth Pullen was practicing in Farmington with Peter Mills. After retiring as Director of the Women's Reformatory in Skowhegan, she had gone to law school in her fifties and was admitted in 1965. Paula Sawyer was in practice in the Lewiston area.

Jean Chalmers, after a civil rights career in Georgia, had just set up on her own in Rockland in 1973. Rae Ann French was an assistant attorney general, having been admitted in 1972. Jessie Gunther, also admitted to practice in 1972, was practicing in Augusta with the Wathen firm.

One thing that distinguishes this group of women lawyers from their predecessors is the high percentage of those involved in litigation. Of their predecessors, I think that only Gail Laughlin handled trial work. Also note that a third of the group are active or retired judges today.

Q: Are you familiar with the histories of any pioneer women in the Maine legal profession?

A: Gail Laughlin was a giant. She grew up in Robbinston, then moved to Portland to save enough money to go to Wellesley College. After Wellesley, she went to Cornell Law School and was admitted to the Bar in New York in 1898. She served as counsel for the Woman Suffrage Association. She practiced in Denver (where she served as state vice-chairman for the Progressive Party) and San Francisco before returning to Maine and setting up practice with her brother in Portland. She worked for the ERA and opposed protective labor laws for women, which often had the effect of barring women from well-paid jobs.

In 1933, she argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court supporting the service of women on juries. She served three terms in the Maine House, another three in the Senate, and served as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee. She last served in the Legislature in 1941. From 1941 to 1945, when she retired, she was the official reporter of court decisions for the State of Maine. Among her other accomplishments was the founding and national presidency of the BPW, which became The Organization for suffragettes post-suffrage. She died of a stroke in 1952 at the age of 83.

There are many others about whom I know little or nothing, except occasional snippets of information. Paul Mills of Farmington, one of the Maine Bar's premiere historians, second only to Judge Silsby, assembled much of the information about the women listed here: Grace Lawton of Lewiston was admitted in 1935 and worked for Skelton, Taintor and Abbott; Alice Parker of Lisbon was admitted in 1932; and Martha Merrill of Union was admitted in 1942. Margaret Sproul of Bristol was a practicing attorney who served in the Maine House and Senate from 1961 to 1969.

Marguerite Fay practiced in Portland in the 40's and 50's. She was a graduate of the Peabody Law School, a proprietary law school in Portland, and served in the Maine House from 1949 to 1953. She served as bankruptcy trustee, briefly.

Paul Mills interviewed Martin Berman and Dean Jewett to find out more about two groups of women lawyers in Lewiston and Saco who practiced from the late 20's to the 50's. Apparently they had started as lawyers' employees who read for the bar in their law offices rather than through attendance at law school. Entry to law school for women prior to the 70's was difficult, even if the candidate had the time and the money, which many didn't. These women seldom or never went to court and were generally regarded by the male lawyers as super-stenographers and paralegals, although the latter term had not yet been invented.

Grace Lawton, Irene Woodhead, and Marguerite O'Roak were the Lewiston group. They typed and took shorthand and worked long hours well into old age, I hope because they found the work interesting. Marguerite O'Roak served as secretary and treasurer of her county bar association for years and offered office space for a short time to the young Frank Coffin.

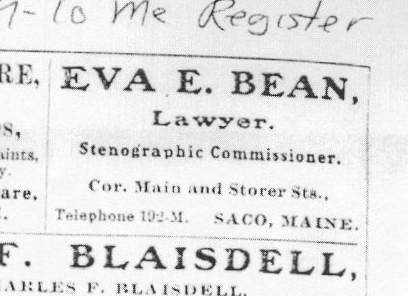

Saco had a similar cluster. In 1927, the Maine Register listed three women practicing there: Mary Bradbury, Margaret Harford Currie and Eva Morgan. In 1934, they were still listed, although it appears that Margaret Harford may have changed her last name to Currie. Eva turns up as early as 1909, then as Eva Bean, and is still reported as late as 1953. She appears to have been the first woman to advertise--in a block ad in the Register of 1909-10. Mary Bradbury read law in her father's office and then inherited the practice. She did some deeds and some probate. Margaret Currie had an active bank title practice and did probate work, not retiring until 1965. She had read law with municipal judge John Deering while she was his secretary.

The 1909 Maine Official Index and Court Directory, published eleven years before women got the vote in Maine, nevertheless lists three women lawyers: Eva Bean and Elizabeth Calley in Old Orchard and Belle Leavitt in Sanford. Belle Leavitt, like many who followed her, was a stenographer in a law office who read law in that office and remained in that office after she took the Bar Exam.

Helen Knowlton entered practice in Rockland around 1899. But it appears that the grandmother of us all, practicing 23 years before any other woman was admitted, was Clara Hapgood Nash of Machias. Clara Nash was admitted to practice in 1872. Judge Silsby published a two-page biography of Clara Nash, with a photo of her, in the April 1972 issue of the Maine History News, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp.9-10. Ms. Nash was apparently the fifth woman to be admitted to the Bar nationwide.

Q: You moved to the upper part of the state to practice law in Presque Isle. When was that?

A: 1985. I moved for love, not for practice.

Q: Is practicing law different for women lawyers there than in the southern part of the state? If so, how?

A: Rural practice and urban practice differ from each other in a number of important ways. Our client base is smaller and less likely to be able to afford as detailed a level of service. Even though we have a shortage of attorneys for the work needed, consistent rainmaking is difficult even for indigenous men. Maintaining the skills and materials necessary to support a general practice is getting tougher every month.

Like everyone else in the state, we face constant change in the rules which govern us and a steady increase in the paperwork, but finding the time to retrain is difficult because so many lawyers are trying to juggle a number of different areas as insurance against the work in one area or another drying up suddenly, as happened in Workers' Comp.

The plus side is that we tend to work with the same people over a long period of time, so we have a pretty good idea of what to expect from each other. Some of us even have each other's sets of divorce interrogatories already in our computers, which saves a lot of time in compiling the answers. We know how our judges (we have two District Court Judges and one Superior Court Justice) have ruled on the issues we are facing. So we can predict the outcome of a particular case pretty well and settle many cases without nearly the hassle that our urban siblings face. The conditions of our daily working life are pleasant, although most of us work pretty long hours.

As for women, we have gone through the same stages women experienced in the rest of the state, but more recently. Of 81 attorneys in the County, 11 are now women. Three of those women I've never met, so I assume they are inactive. Of the eight who are active, four are in private practice. Most of us have been practicing here for years and acceptance is good among other attorneys and the Courts. What I don't think is strong in our area yet is general private client acceptance among those who can afford full legal services.

Women need to find a niche market to survive economically. If the movement to unbundle legal services is successful, though, I think that change may provide opportunities to define more niches.

Q: When was the first woman judge in Maine sworn in?

A: That one's easy. Harriet Henry as District Court Judge in the fall of 1973. One aspect of research we should look into in the future, though, is whether any women served as municipal court judges during the period that system was in place. I tend to doubt it, though.

Q: As more and more women enter the legal profession, are changes occurring in how law is practiced? Are women changing the law?

A: I hope to heaven that we don't get blamed for the seismic changes in the practice of law that have occurred in the last 27 years. Prior to this most recent period, about the biggest change that took place in the practice of law during the comparable preceding period was the adoption of the Civil Rules.

Since 1974, the changes in the practice of law have been explosive. Like the schools, the courts have taken on functions that they were never designed to handle and it remains to be seen whether the client population will actually benefit. The public perception of our performance doesn't seem to be improving just yet. Right now we seem to have major disjunctions between the Courts' perception of its role and lawyers' perceptions of theirs. I don't think that's healthy for the long haul.

There is no question that, as more and more women enter the legal profession, changes are occurring in how law is practiced. As lawyers, we are trained to recognize that concurrence does not prove causation, however.

Q: Have we made giant strides or are we just beginning to catch up?

A: From 18 women to 1000 in 27 years? That's 982 giant strides. I think we all ought to have a big celebration soon for having hit our own millennium. I called the Board of Overseers this morning to get the current census and I haven't been able to wipe the smile off my face all day.

Q: Did the women's movement of the Sixties make a difference for you in the Seventies?

A: Oh, yes. All that consciousness-raising looks foolish now, but we who were brought up in the Forties and Fifties needed intensive de-programming and a heavy dose of reality. That is really what was going on, de-programming on a society-wide basis.

The women's movement spared many of my generation what could have been a lifetime of discontent, the life many of our mothers were leading. It gave us courage to act and great daycare to enable us to act. I doubt very much that the law school would have been willing to accept a mother of young children had not the movement eased the way. I and many others were swept along by that big wave and it has made all the difference.

Q: What is your advice to young women considering going to law school?

A: My experience of that is too outdated to be useful in any detail. Some things remain constant, though. The best academic preparation for law school (and perhaps the best predictor of success in law school) is mathematics, philosophy, music and the study of languages which involve the use of another alphabet. Avoid "pre-law" courses altogether. Note that they are usually taught by non-lawyers.

The best practical preparation for law school is a year of accounting. A year of economics and a semester of statistics wouldn't hurt either. Work enough with computers to become fond of them and keep up with the literature so that you can become an early adopter in your study and in your practice.

Q: What can be done now to bring about gender equality in the future?

A: First, a word of comfort. You will probably experience gender equality in your lifetime just by aging. From the time a woman lawyer hits fifty until she starts to drool in public while awake, she doesn't get offered much guff. That's why many professional women interviewed on retirement state that they've never encountered bias or prejudice during their careers. They've just stuck with it so long that they've forgotten those experiences or they've fossilized the denial they needed to survive. Forgive them, because they've helped us enormously just by being there.

Even so, every now and then it still happens, though I'm well over 50. I'm in a Chambers conference and I offer a solution to a problem. There is silence. Then a man offers the same proposed solution in slightly modified language. The assembled group, all male, says Aha! That's the answer!

In microcosm, that particular sort of male bonding is the source of the continuing problem. And the only cure I know of is to get at least one other woman into that Chambers conference. We are solving the problems of gender inequity simply by increasing our numbers. We women are good at that.

END